A Georgia-based brokerage has settled allegations that it and its president developed and sold a trading strategy that they did not understand and that caused near-total losses for 350 clients, according to the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority as reported by Financial Advisor Magazine recently. The brokerage had agreed to $2 million in partial restitution to those clients and a censure. The former president agreed to pay $15,000 and accepted two concurrent suspensions from dealing with the industry for more than a year. There are no allegations the firm was not intending to act in the best interests of their clients. It seems clear that the firm, and the former president, did not understand fully how the product worked. The full article can be read here https://www.fa-mag.com/news/georgia-b-d-to-pay–2m-to-clients-for-allegedly-selling-unsuitable-products-80231.html

All 5,200+ stocks US and Canadian stocks, 16 sector groups, 200+ industries, and 600+ ETFs have been updated:

Two-week free trial: www.ValuEngine.com

The product in question, the Daily Inverse VIX Short-Term Exchange-Traded Note, had the ticker symbol XIV. It was structured as an Exchange-Traded Note, sometimes called an ETN. ETNs are essentially structured products that are issued as senior debt notes and trade as stocks. They have credit risk linked to the issuer which may or may not be the note’s sponsor. They are designed as trading vehicles but own no underlying stocks or bonds. However, despite having no structural commonality with mutual funds, ETNs are frequently categorized as ETFs and lumped in with ETFs in stock price quotation listings in financial media.

The Exchange Traded Note in question was issued by Credit Suisse and sponsored by DirexionShares, an ETF issuer that specializes primarily but not exclusively in leveraged ETFs and structured notes. For many months since its introduction, the product had produced excellent weekly price gains with low price volatility. As long as VIX, CBOE’s volatility index on the S&P 500, had no sudden upward spikes, XIV provided small but steady weekly gains. Unfortunately, the calculation of the note resulted in an exponential loss caused by a huge spike which wiped out years of gains and more in one day. Many financial advisors are not experts in the mathematics behind structured notes and potentially severe one-day price movements. The vast majority of advisors’ clients and retail customers typically have even less understanding of them.

Current ValuEngine reports on all covered stocks and ETFS can be viewed HERE

How could this happen when ETFs are generally considered prudent investment vehicles and are backed by the securities they own? At the heart of the issue is the fact the “F” in the term ETF refers to “fund.” True Exchange-Trades Funds (ETFs) ARE mutual funds, a fact that various investment publications continue to misunderstand and get confused by. ETFs have the same applications and requirements as other mutual funds and are similarly governed by the Securities Act of 1940. Like other mutual funds, they can be index-linked or actively managed. The major differences are that most shareholders buy or sell ETF shares through brokerage accounts whereas traditionally structured mutual funds are bought or redeemed daily through the mutual fund’s distributor. ETFs have an exemption to the “redeem daily at the distributor for cash on demand” provision.

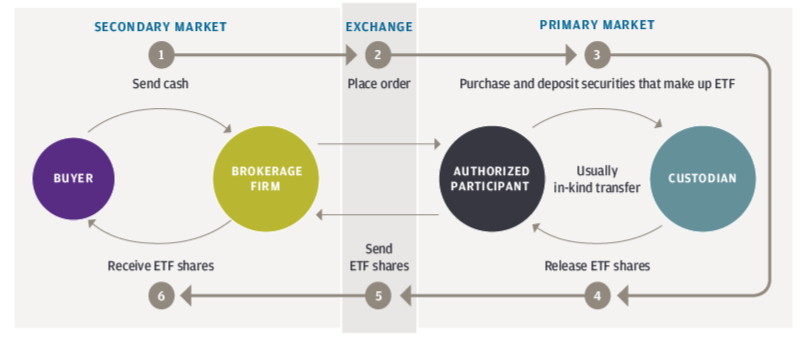

The major twist with ETFs is that while new fund shares can be created or redeemed daily with the distributor, they can only be created and redeemed through authorized participants in very large quantities, generally at a size of more than $25,000 per transaction. These participants buy tens of fund shares at a time. For equity ETFs, they typically do so by contributing baskets of “in-kind stocks” requested by the fund. They can be thought of as miniature replicas of the fund’s constituents in the proportion held by the fund. To sell fund shares back to the fund itself, participants send the requested amount of fund shares per basket to the fund and receive baskets of the underlying securities in return. This diagram is a big picture view of the process.

This complex-sounding redemption process, now done routinely every day, is considered a free-receipt-and delivery process. Unlike selling securities for cash, the free-receipt-and-delivery process is not subject to capital gains tax. Thus, ETFs generally do not need to make capital gains distributions to fund shareholders as traditional mutual funds do.

Beyond taxation, the exchange-traded fund structure holds many advantages for both fund shareholders and fund companies. To learn more, please read “Leveling the Playing Field for Active Managers” available on the ValuEngine site at https://ww2.valuengine.com/research-library/

Financial Advisory Services based on ValuEngine research available: www.ValuEngineCapital.com

This begs the question, “If ETFs are just more efficiently structured mutual funds, how do ETNs and other vehicles such as grantor trusts and commodity pool shares get confused by investment professionals with ETFs? The ultimate answer is by failing to read and understand the summary prospectus. This is something any investment professional should be expected to do automatically before buying or selling anything on behalf of a client. Unfortunately, I have been stunned how often these products are bought on exchange without doing so. Judging the safety or suitability of an investment product solely based upon its name and historical performance data is a prescription for disaster.

In my years as a consultant, I have run into many cases where investors and traders simply do not understand math behind inverse and leveraged ETFs and the implications of that math on return streams. Frequently, the expectation is that if I buy an inverse 2X S&P 500 ETF on May 31 and the Index goes down 5% in June, I should gain 10% for the month. In reality, the mathematics behind daily futures compounding works very differently. No one should buy or sell products that buy or sell daily index futures as buy and hold tools. They are designed for daily or hourly trading.

Another part of the confusion is the term “ETF wrapper.” It is used in almost every investment webinar I attend these days. “Wrapper” has no standing in investment law or with the SEC. It actually comes from old mutual fund jargon about different classes of fund shares offered to differentiated types of investors (e.g., 401K plan, High New Worth, etc.). Since all types of investors have equal access to buy and sell ETF shares at the same price and fees and tax treatments, the word “wrapper” shouldn’t really apply. Moreover, I believe it demeans the actual structural advantages of the Exchange-traded-fund. At any rate, “experts” describe mutual funds now structured as ETFs as “being in the ETF wrapper.” Unfortunately, they also describe many other products as ETFs with the justification that “they use the ETF wrapper.”

Using ‘ETF’ to describe something not associated with a mutual fund is not a new sleight-of-tongue. Experts have done it for years over the objections of investor education advocates.

The trend really became in vogue with GLD, a depository receipt on physical gold, launched by State Street Global Advisors in cooperation with the World Gold Council in 2003. The structure was modeled after an ADR using the legal vehicle of a special type of trust called a Grantor Trust. A share of GLD is a share of a trust that can hold precious metals, currencies, foreign stocks, land deeds and many other things. The shares trade on stock exchanges. Upon sales, investors are taxed as if they had sold a pro rata portion of the underlying assets. Thus, they do not have the tax advantages of ETFs but a different tax treatment altogether. There is no underlying mutual fund and no portfolio manager. However, ETFs such as the fund based on the Nasdaq-100, QQQ, and the one based on the S&P 500, SPY were gaining in popularity at this time. They were starting to catch financial advisor’s imaginations as investments that allowed institutional index products to trade like stocks, thus democratizing investing. State Street, iShares, Vanguard, and First Trust were among those actively visiting planners and advisors on how ETFs allowed access to different asset classes in a single trade. Once GLD allowed gold to be traded just like a stock, the investment media and many industry professionals viewed it as an extension of the ETF revolution. The distinction that GLD had a completely different structure with a different tax treatment seemed unimportant compared to sharing a good story about another exchange-traded product that changed the face of investing.

Current ValuEngine reports on all covered stocks and ETFS can be viewed HERE

This watershed event explains how products reflecting non-traditional-assets-with-financial-value that use the Grantor Trust and similar structures are now commonly called ETFs despite the fact that there is no actual fund associated with the product. Other products called ETFs with no fund include:

- Other Exchange-Traded Metals such as SLV (silver), also a Grantor Trust;

- Exchange-Traded Commodity Pools such as USO for oil and UNG for natural gas;

- Exchange-Traded Notes such as AMJ, JPM Alerian MLP;

- Limited Partnerships using offshore funds holding derivatives and swaps such as BITO, ProShares Bitcoin Strategy Fund;

- Exchange-Traded Bitcoin, IBIT, and 9 others – using the same Grantor Trust Structure as GLD.

Tax treatments are another very important reason to make a distinction between ETFs, Grantor Trusts, Commodity Pools, Structured Notes, Managed Futures Products, Funds Incorporated Offshore and other products. For the first example, let’s take GLD which as mentioned above is a Grantor Trust.

A grantor trust is ignored for tax purposes so that the investor is treated as owning a pro-rata share of the underlying holdings, not the entity. If GLD were a mutual fund, it would be taxed ‘normally,’ but because it is a grantor trust, its long-term gains are taxed as a collectibles gain – at the 28% rate.”

Many tax-filers intensely dislike receiving K-1 filings. First, the form often requires that you take several different numbers and include them in various places within your regular tax return. The other inconvenience of the K-1 is that different companies are inconsistent about when they send the forms out to their investors; this often causes delays in being able to file the tax return.

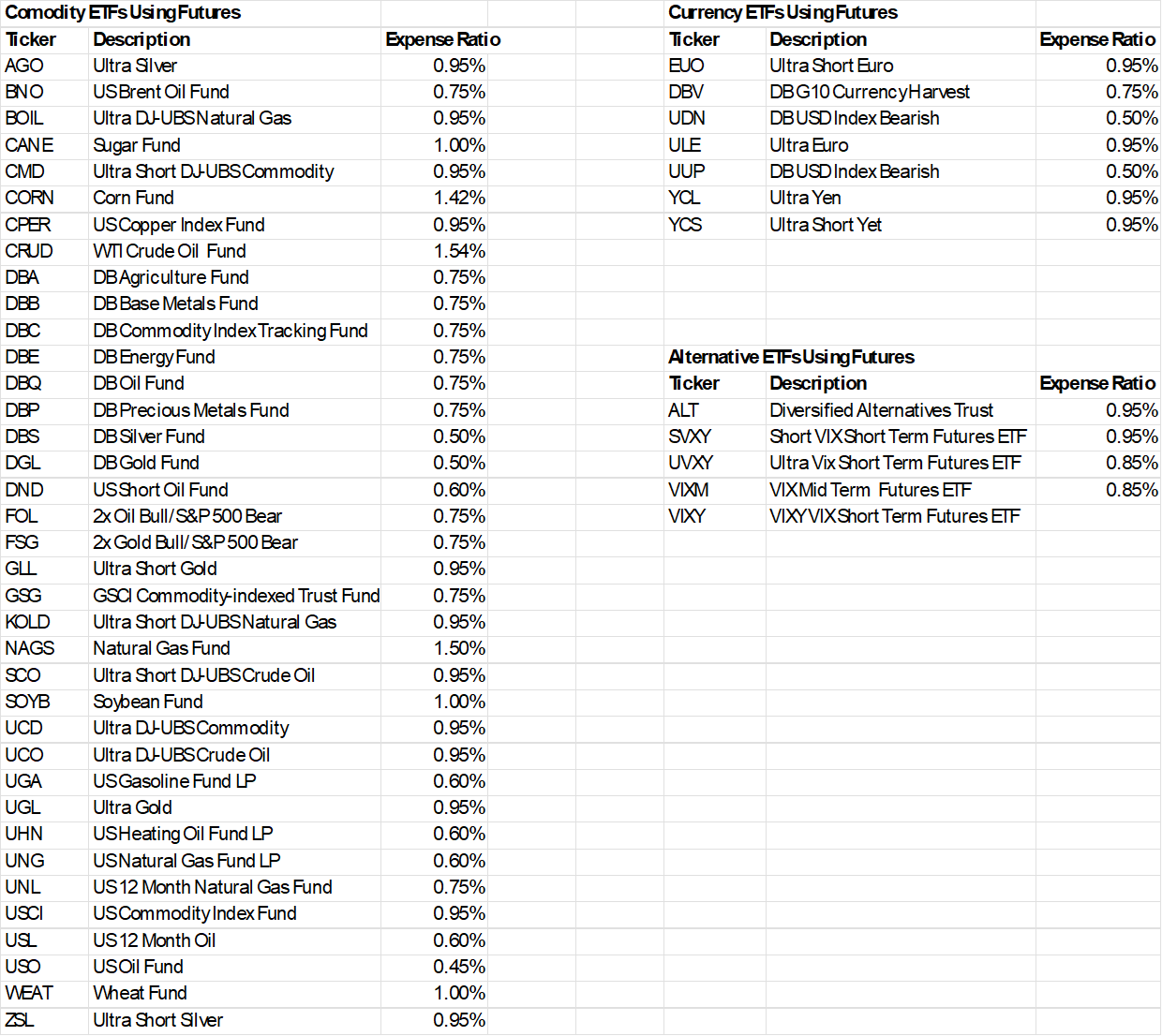

Commodity pools issue K-1s. At least 36 Commodity “ETFs” that are actually shares of ownership in a Commodity Pool partnership issue K-1 forms. Beyond these examples, 7 currency funds and five alternative investments that use futures to enhance returns and/or income also issue K-1 forms to shareholders.

Limited Partnerships that issue exchange-traded shares also must issue K-1 forms. Alternatively, Exchange-Traded Notes (ETNs) such as AMJ do not need to issue K-1s, but they do carry counterparty risk. When sold, they are not taxed at capital gains rates but as ordinary income. The conclusion is that when it comes to products “in the ETF wrapper,” it is probably a good idea to ask a tax specialist before buying and selling these instruments. No one wants to receive unexpected K-1s.

The list of exchange-traded products that issue K-1s:

Current ValuEngine reports on all covered stocks and ETFS can be viewed HERE

Education and due diligence are the keys to avoiding tragic consequences such as the ones suffered by this advisory firm and their clients. Just because something is popularly called an ETF, such as GLD and USO, does not mean it is structured as an ETF. With leveraged ETFs and ETNs that use futures and complex structured notes, knowing exactly what is being traded is essential. The summary prospectus is not an especially long or complex document. It should be common sense not to buy, sell or recommend any investment product too complex to understand. In fact, it took ProShares, the first major ETF firm to build futures ETFs, five years to get SEC approval because the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) objected profusely. After all, to trade futures, one must demonstrate that he or she is a qualified investor but anyone, no matter how unsophisticated, can trade an investment product that trades like a stock. The CFTC’s investor protection argument was widely disregarded as a “turf war” issue and perhaps it was. However, this case shows that there are also legitimate concerns with products that in the wrong hands have the capability of turning into weapons of wealth destruction.

This is why Schwab and Fidelity, among others, display the universal warning sign, a yellow triangle with an exclamation point inside to alert clients about purchasing some of these products, that they are intended for professionals, and ask if you are sure that you understand them and wish to proceed. One major mutual fund company’s brokerage arm will not allow its clients to purchase such products on their platform at all. This is probably too extreme, but the concerns are certainly valid. As Captain Furillo used to say on Hill Street Blues, “Be careful out there.”

______________________________________________________________

By Herbert Blank

Senior Quantitative Analyst, ValuEngine Inc

www.ValuEngine.com

support@ValuEngine.com

All of the over 4,200 stocks, 16 sector groups, over 250 industries, and 600 ETFs have been updated on www.ValuEngine.com

Financial Advisory Services based on ValuEngine research available through ValuEngine Capital Management, LLC

Free Two-Week Trial to all 5,000 plus equities covered by ValuEngine HERE

Subscribers log in HERE